Plants, unable to move or speak, share information through scent.

As you know, plants cannot move. They can rustle their leaves but cannot speak. However, they definitely communicate with each other, for instance, by releasing volatile compounds, like scents, to share information with nearby plants. The scent carried by the wind allows one plant to share information with another.

When in danger, the composition of the volatile compounds they emit changes.

Plants constantly release volatile compounds. For example, near rosemary, you can smell the spicy scent that goes well with meat, characteristic of rosemary. The scents of herbs and flowers are part of the volatile compounds released by plants. Normally, plants emit scents for their own benefit, such as attracting insects with pleasant fragrances to improve pollination efficiency or repelling insects by emitting compounds with insecticidal properties.

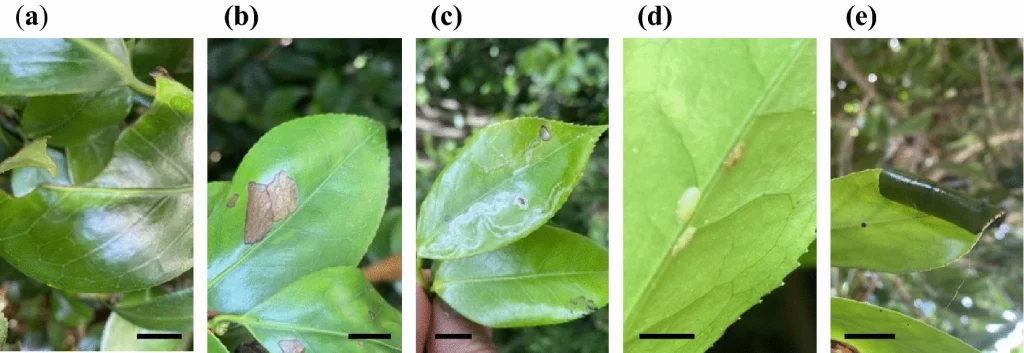

Sometimes, due to insect damage or disease, a plant’s branches and leaves can get damaged, and when that happens, the composition of the volatile compounds it releases changes. This change in volatile compounds can enhance the stress tolerance and recovery ability of the unaffected plants that perceive the scent.

In other words, when damaged, plants are essentially telling their neighbors, “Prepare yourself, as the same might happen to you.” They might even be raising an “alarm” to notify others.

Plant–plant communication in Camellia japonica and C. rusticana via volatiles

“Using plant screams to strengthen other plants” business

The volatile compounds contributing to this communication have not yet been identified and could be multiple compounds. Future research is anticipated. If these substances can be identified, it might be possible to minimize damage by “preparing” plants in advance for disease and pest attacks. Additionally, because these substances are derived from plants, the barrier to using them on food might be lower. Since they are volatile compounds, their effectiveness in closed environments like greenhouses, or even outdoors, and other practical aspects of their use might become clearer with further research.

In the future, agricultural pest and disease control might not only involve spraying “liquid” pesticides but also applying “gaseous” components, which could become a common practice.

コメント